According to Travel+Liesure,

- - - We are such an interesting species. Consciously or subconsciously, collectively or individually—we take moments (days, seasons), add demarcation lines, milestones, benchmarks, candles, and sparklers, and we render those moments meaningful—even though there is no intrinsic meaning. The act is both pragmatic and ritualistic. It's a way of marking the passage of time—of focusing our collective gaze on the past, the present, and the future. It's a way of validating a principal. It’s an acknowledgment of change. We consecrate moments because they represents achievements. Because they represent hard work and success. Or, conversely, because they signify the end of a painful or arduous time. We consecrate moments because, at essence, they harken to our primordial condition as participants in the cycle of life. And yet we transcend the primordial; we’re meaning makers. We accentuate meaning when we feel it is inherent in a moment; we create it when there is a void. We do this, universally. This is one of the fundamental differences between humans and all other sentient species. Whether consciously or not, we clothe quotidian times in the vestments of ritual and the cloaks of ceremony. The autumn harvest transfigures into a moment of collective gratitude. We take the longest night of winter, and recognize its spiritual resonance, aligning it with salvation, and hope, and rebirth. Spring is the manifestation of that hope, the triumph of life, and we dress vibrantly to mimic renewed vitality. When In the midst of broiling summers, we celebrate freedom—individual, political, and seasonal. We’ve emerged from our cloistered winter quarters because the weather whispers “Come out and roam and play.” And with autumn, the cycle complete, we retreat again to our dens of contemplation and gratitude, knowing that life is the mythical phoenix; it must die before it can be reborn. We take a birthday—a moment every living thing experiences—and add cake and streamers and tributes; we elevate the individual. We witness processions of our youth in late spring, in the customary vestments of the learned, away from one phase and into the next. We cannot escape the inexorable gravity of meaning. It’s like an automatic reflex, akin to blinking and breathing. And, I think, equally essential. The attribution of meaning transfigures mundane experience. Birthdays become significant because they allow us, encourage us, to mark our own passage, to take stock of ourselves as we journey alongside multitudes. Graduations make palpable youthful milestones and benignly echo the life cycle. Once loathe to reflection, our children, in a strange and beautiful temporary stasis, recall with melancholy the passing of their youth and anticipate, with trepidation and enthusiasm, a promising future. - - - The New Year is one of these Interesting moments that humans have festooned with light and sound and appropriated for a host of various reasons. People revel with intimate groups or in multitudes, sending off the old year and ushering in the new with celebrations and intention—positive “first-footings.” Others view it as a symbolic baptism. We are cleansed, sharpened, and ready to write another chapter. For as long as I can remember, my father has encouraged us to preserve a handful of allegedly Greek New Year's traditions. Now, whether or not they’re legitimately Greek is debatable; the Greeks are a quirky lot, but often these seem like realities borne of a blow to the head. Regardless, after 30 years of these traditions, I suspend reason and participate with conviction. This is like a multi-step equation, and—I assume—order is critical; it has its own PEMDAS.

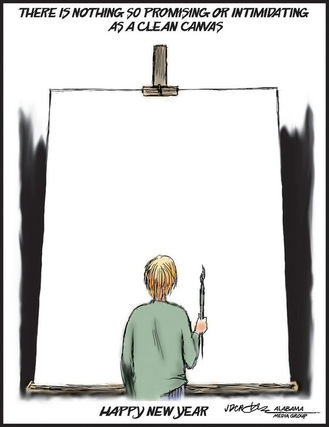

And so, in this ritual our father has taught us, which we have rehashed for as long as I can remember, which has been the subject of phone calls when we’ve been apart ([I'm in Windsor, Canada] “Happy New Year’s, Dad! Have you turned on the faucets? Where are you right now? Don't forget to go out and spit! Don't worry; I just peed in the bushes. Yes, they saw me. No, they think it’s perfectly normal…”), we’ve created our own meaning, appropriately aligned with the perspectives of others. These are our torches, our leaps, our scary noises and gunshots! This is a global phenomenon, each region embracing its idiosyncrasies while adhering to the same blueprint. For one moment one New Year’s Day, many of us reflect on the past year with lamentations and relief, and on the infant year, laid out and bare on the examination table for a first look. Because of our rituals, our symbolic cleansing and preparations, we are bursting with hope, and we are justifiably moved. We are equipped through our symbolic gestures that are at once completely meaningless and completely meaningful. We are emboldened to attack the year with resolutions, with vigor, and with the optimism of youth because we are born again, having been baptized by running sinks and the flushing of toilets! Yes, we resolve impossibilities, but what a noble, if quixotic, endeavor! Why not pledge to loose some weight, to do more volunteer work, to build bridges over chasms? At worst, we'll have made incremental progress--or failed and learned. We strive to meet our best selves and we hope for the best in others. We are unified, globally, in this sentiment, as if the collective unconscious, for this one night, becomes ineluctably manifest. And that's why New Year's, although just another day in the rotation and revolution of the earth, is so meaningful. Because it is a collective endeavor. It shines the spotlight on humanity. We hold hands and march; enriched by our diversity, we march forward to face progress, to face new challenges, and, hopefully, to do it better than the year before. A universal idiom. Niko Tsivourakis Global Initiatives Director

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorThis blog is the collective voice of every person involved in the Global Initiative. Just as the globe hosts billions of disparate voices, we hope this space will embody and embrace the same diversity. Archives

July 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed