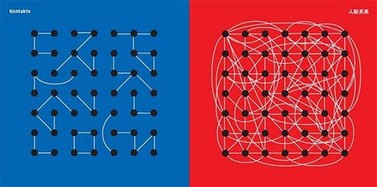

The Japanese fans stayed late. Motley and jaunty, they’d just beaten heavy Group H foe and international favorite, the Columbian national team in a World Cup showdown. They had work to do before leaving the stadium. The reveling could wait. See, like guests in any stadium, they had drinks and snacks, used cups and straws, and blotted mouths and greasy fingers with napkins. Like any fan, they tossed the refuse on the ground, clearing it away during the 90 minutes of standing and jumping, cheering and chanting. Most of the sport-loving civilized world stands and queues out of a stadium, leaving their trash behind for the stadium staff to collect and dispose. There is no fault in that. People are hired for this purpose. This is the protocol, which most happily embrace. Like an elegant equation, my presence and actions necessitate the work of another, whose work reflexively frees up my hands and time, and is included in the price of admission. What we neglect, however, is that this is indicative of an epidemic among so many in the developed and the developing world. We are gratuitous consumers and prodigious producers of trash. I recently read a fascinating critique of consumption in the modern world, particularly in the Age of Amazon, when anything can be purchased at any time, often with just “one click.” In it, I learned that we in the modern West buy 7.5 pairs of shoes a year! Partially asleep with phones still in our hands, we make midnight impulse purchases for content that we neither need nor use. This isn’t a new phenomenon, but mobile devices make it easier. (Disclosure: years ago, late at night, I ordered the compilation Pure Moods. You know what I’m talking about.). We tend to hold onto unwanted gifts and unwanted online purchases, and they go to the closet, forming a new stratum on the junk heap—the cross-section of which revealing decades of purchases, culture, and values. Think of everything you’ve bought that’s resigned to history. Think about what you did with it. I’m embarrassed. Everyone must be a buyer in modern economies. We need certain things to survive, and—politics and complicated economic theories aside—our purchases fuel the economic engines, which bring wealth and prosperity to individuals and nations. But how much we should buy and how often are moral and ethical quandaries. An unintended consequence of all that consumption? Trash. Trash beyond measure in allocated spaces. In un-allocated spaces. Washing up to shore. Wandering through the country on trains. Floating in a swirling mass four times the size of Texas in the Pacific. Most of the trash comes from perfectly decent folks who care for the environment and are vigilant in their decision making. But the ease of on-demand consumption, with the convenience of just throwing something away, rolling it to the curb to be rushed out of sight, divorces us from the next steps—the consequences. Coupled with the ease of the “buy now” button, disaster germinates. When I clean up my own mess, when I must handle the detritus of my daily life, I’m staring at the refuse of my choices. And it’s not just an individual’s consumption. We see it in our hunger for electricity and the consequential emissions and coal ash. We see it in our thirst, our water needs, and the effects on reservoirs. It’s a reckoning-- humbling, a little painful, and very instructive. The Japanese make loads of garbage! It's an island chain with a huge population. Tokyo pulses in the worlds largest metro area (30+ billion people). I can’t conceive of either the waste or the mechanisms to handle it. But the Japanese value cleanliness, order, and respect. These people, at the confluence of so many forces, including a limited and tenuous geography, clean up after themselves. The are sensible consumers. They respect moderation, their land, and each other. To those ends, they have novel solutions to big problems. They clean up after themselves. They moderate their purchases and consumption. They incinerate, recycle, and repurpose their waste. Keeping in mind their area’s size and population density, they make decisions with their collective footprints in mind. Most importantly, this is a mindset that follows them as they venture outside of their boarders. Those fans weren’t doing this for press. To be aware of their physical footprint and minimize it is second nature. They are for the rest of us, they are roll models of good practices done for with the best intentions. The cultural divide between the East and the West may be shrinking with global-everything bridging the gaps. Of what differences remain, we could debate the relative strengths and weaknesses. And it’s certainly silly to presume homogeneity. Proof? K-pop. But I do think there is one benefit of the Eastern disposition towards the collective with which we often struggle in the West. When I perceive myself as one among many in much larger, complicated networks, I have to think about my impact on the group. It’s a built in mechanism to defeat the Tragedy of the Commons. Selfless actions, born out of an emphasis on the collective, tend to bring greater good to the greatest number. The Japanese fans indulged in crazy revelry the same as everyone else, but that was only part of their experience. There is a time to splurge, indulge, and carouse; but there must also be time to clean up. Niko Tsivourakis, Director, The Global Initiative

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorThis blog is the collective voice of every person involved in the Global Initiative. Just as the globe hosts billions of disparate voices, we hope this space will embody and embrace the same diversity. Archives

July 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed